Ethics Framework and Guidelines:

Table of Contents

Ethics Framework and Guidelines »List of Abbreviations »Preamble »Introduction »

Part I: General Consideration »On ethics »General considerations on ethics »Ethical assessment procedures and the ethics review »On participation »General considerations on participatory practices »Experiences with the ethics framework »

Part II: Tools & Guidelines »A. How should participatory processes be structured? »B. Which type of activity is targeted by the participatory process? »C. Which types of participants are targeted? »D. What are ethical issues and risks? »E. How can equal and meaningful dialogue be fostered? »F. How should participatory processes be monitored & reflected upon? »

Glossary »EC Reference Documents »Endnotes »

On participation

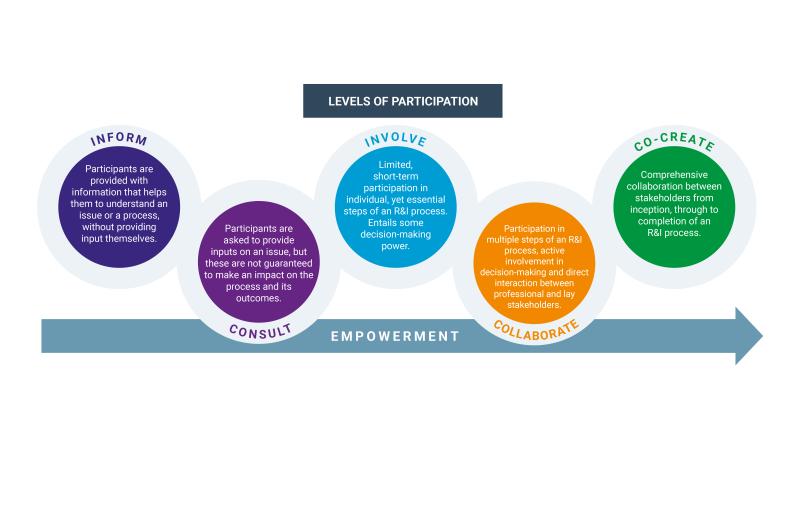

This ethics framework is aligned with the European Commission’s strategy on research and innovation, which aims at “strengthening a common ownership of research and innovation policy and promoting the common research and innovation values” through the co-design and co-creation of R&I activities13, 14. Participation is a crucial part of movements such as Responsible Research & Innovation15 and Technology Assessment16. While there is no uniform definition, participation is frequently described as a form of engagement that allows (potentially) affected stakeholders to partake in decision-making for R&I17. Following the many theoretical approaches building on Arnstein’s ladder of participation18, truly participatory practices are arguably different from other engagement practices in that they empower stakeholders to varying degrees to shape decisions in accordance with their own values and worldviews. In this, there is a trade-off between the possible control exercisable

by researchers, funders, policymakers, and so on, and the level of empowerment experienced by other stakeholders. Participatory practices are further distinct from other engagement forms as they require two-way communication between the participant and decision-maker19. Thus, when structuring and implementing a participatory process, there are many decisions to be made, all of which have ethical implications.

There are numerous supporting and opposing arguments for participation20. As discussed in our overview on ethics, participation is needed to identify and weigh ethical considerations to arrive at more socially desirable and ethical outcomes. Participation is furthermore supported by the assumption that tackling complex public problems requires collective decision-making to foster more effective outcomes21 (substantive rationale). What is more, participation is often argued to enhance the trust in, and the legitimacy of, R&I. Stakeholder participation may also lead to an increased support and adoption of outcomes (instrumental rationale). From a democratic perspective, participation may

moreover be considered ‘the right thing to do’ as potentially affected stakeholders can influence how their lives are being shaped (normative rationale). Yet, participation is not always deemed desirable and is often opposed by those who consider that scientific work is already exposed to many constraints both internally and externally (e.g. international competitiveness).

The relationship between participation and ethics can be complex and ambiguous. It differs in each instance, depending on the chosen approaches, types of stakeholder, and aims of the decision-making process. Examples of possible approaches include participatory evaluation, citizen juries, consensus conferences, deliberative opinion polls and citizen advisory committees. While participatory decision-making processes can aim to achieve consensus or compromise, they might also allow for (productive) disagreement as a result of an activity.

Another key issue to address when implementing participatory processes is who exactly should be engaged. Participatory processes are increasingly targeted at “citizens” or “stakeholders“ – terms which are not synonymous, nor do they represent the whole array of potential participants. In any case, it is important to be aware that the terminology chosen for prospective participants has consequences for who may be included – and who excluded. Thus, the language used must be critically reflected and chosen carefully22. For instance, “citizen” also has a legal meaning tied to nationality which might not be intended when employing the term in a participatory process23. Participants can be of various kinds, extending beyond the traditional expert (scientist or researcher) and including, for example, experts by experience and civil society representatives. Other categories essential to consider, both when defining a stakeholder group and when engaging a specific group of participants, include gender, dis/ability, socio-economic background, age, geographic location, and ethnicity. The relevance of different groups of participants will vary depending on the exact context of the process.

In light of the various definitions, rationales, approaches, roles, and types of participants, a taxonomy is presented in this ethics framework as a guideline and common reference point for our working definitions.

PRO-Ethics identified several needs of RFOs employing participatory approaches. These relate to: the definitions of participation and ethics in R&I; ethical dimensions and potential issues; ethical risks and their mitigation; the need for checklists specifying what to consider when involving participants; and considerations regarding ethical challenges, (structural) biases, and points of attention. Specific issues have also been identified when different interests and types of knowledge intersect, as well as in terms of the methods to be employed. Subsequently, participation should be approached in the context of each individual case, and with appropriate questions addressed.

The perceived benefits and legitimacy of participatory processes differ among stakeholders. There are various factors that play a role in participation, such as: the needs of RFOs and the resources at their disposal; the potential modes of participation and their appropriateness to the task; and the ethical challenges and issues of participation critical to RFOs (identification and representation of participants, avoidance of biases, use of personal data, etc.). All these factors were considered when developing the tools and guidelines in this ethics framework.