Ethics Framework and Guidelines:

Ethics Framework and Guidelines (EN)

Ethics Framework and Guidelines

Table of Contents

How should participatory processes be structured? Which type of activity is targeted by the participatory process? Which types of participants are targeted? What are ethical issues and risks? How can equal and meaningful dialogue be fostered? How should participatory processes be monitored and reflected upon?

Introduction

As participatory engagement practices are increasingly recognized as a valid and often necessary dimension of research and innovation (R&I) – and specifically the work of research funding organizations (RFOs) – the need to establish strong ethical parameters and guidance for the implementation of such approaches is more important than ever. The work of PRO-Ethics has shown that established ethics review procedures are often unable to grasp the complexity of participatory processes, while the focus on compliance with existing legal and ethical regulatory frameworks fails to address the nuances and tensions of evolving multi-stakeholder processes.³ As a result, decades of participatory research have emphasized the importance of understanding the concrete context of implementation when setting up and realizing a participatory process.

The ethics framework consists of tools and guidelines that support the ethical organization of stakeholder participation by respecting each processes’ specificities. In the context of R&I funding, this document aims to operate as a standard for organizing participatory processes and addressing ethical issues and risks before and while they arise. This entails both research ethics in the broadest sense, and the ethics in and of participation more specifically. The framework addresses the diversity of views on ethics and participation, the specific practices of RFOs, and important contextual questions, such as: How is participation justified? What are the expected goals and outcomes? And what are the underlying ethical issues?Over four years, the PRO-Ethics project encountered a diversity of practices and understandings among actors in how to approach the ethics of participation. This framework aims to combine these different approaches into a comprehensive step-by-step guide for ethical participation in the activities of RFOs. As such, it may also prove valuable for other organizations interested in ethical participatory processes, such as research performing organizations, research ethics committees and research integrity bodies. It provides questions to address in each stage of a participatory process – from its preparation and implementation to its evaluation. It also covers different contexts of implementation and guides the user to meet their differing requirements. Furthermore, it is compatible with, and complementary to, other frameworks, standards, and codes of conduct used in the context of R&I.

This document consists of two parts:

- A general description (theoretical introduction) of the framework’s scope, objectives, and positioning, and how it should be applied. This part also includes experiences of RFOs using the framework.

- Tools, guidelines, and a glossary. The tools and guidelines offer “actions” to be considered for ethical stakeholder participation before, during, and after the implementation of participatory processes. Although they were developed for RFOs, they are relevant for broader audiences within R&I.

Part I: General Considerations

On ethics

There is broad consensus that R&I has a substantial impact on society. Innovations are not value-neutral but rather impose certain values, worldviews, and risks on society. By way of illustration, let us consider the possible implications of Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI is often associated with positive impacts such as the automation and optimization of tasks like fraud detection, quality control, and medical screenings. However, algorithmic decision-making also entails certain risks such as biases and discrimination, data misuse, and shifting job markets. These risks are subject to heated debates and show that ethical considerations are needed to ensure that R&I processes result in socially desirable and ethically acceptable outcomes.4 This is especially urgent for ex-post ethical guidance for innovations already developed and embedded in society.

Researchers increasingly urge for early anticipatory and reflective deliberations that help collectively shape innovations when this is still possible

OPEN SCIENCE

"Open science is a set of principles and practices that aim to make scientific research from all fields accessible to everyone for the benefits of scientists and society as a whole. [...] Open science has the potential of making the scientific process more transparent, inclusive and democratic.”

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

CITIZEN SCIENCE

"Citizen science is an ‘umbrella’ term that describes a variety of ways in which the public participate in science. The main characteristics are that: (1) citizens are actively involved in research, in partnership or collaboration with scientists or professionals; and (2) there is a genuine outcome, such as new scientific knowledge, conservation action or policy change."

European Citizen Science Association (ECSA)8

TRANSDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH

"Transdisciplinary research [...] is a mode of research that integrates both academic researchers from unrelated disciplines – including natural sciences and SSH – and non-academic participants to achieve a common goal, involving the creation of new knowledge and theory. In drawing on the breadth of science and non-scientific knowledge domains such as local and traditional knowledge, and cultural norms and values, it aims to supplement and transform scientific insights for the good of society. It criss-crosses the traditionally separated realms of science and practice and advances both simultaneously."

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)9

RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH & INNOVATION

"Responsible Research and Innovation is a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society)."

René von Schomberg (2011)¹0

The multitude of ethical theories suggests there are several ways in which ethics can be considered in R&I. For instance, ethics can focus on particular types of entities (i.e., action, person, institution, technology); normative factors (i.e., values, consequences, virtues or norms); and foundational normative theories (ways to select normative factors and types of entities). Conflicting factors or hybrid forms of reasoning call for a move beyond regulations (as in ethics reviews/assessments), and to embrace a broader pluralistic scope. These views demand enhanced reflexivity and responsibility. Especially related to the development of digital technologies, we have also witnessed a rise of specific design approaches that are sensitive to specific values (value-sensitive design, human-centered design) or specific challenges (explainable AI, human-in-the-loop design), or the broader functioning of digital technologies (trustworthy AI).

Ethical compliance and appraisals such as ethics reviews in research funding tend to stay close to legal standards and regulations and in turn do not comprehensively cover intricate ethical conundrums as they arise during complex R&I processes – especially if they are structured as participatory processes. Publicly funded R&I is associated with forms of ethics assessment procedures, safeguarding the compliance of (to be funded) research with ethical principles. However, ethics reviews differ across countries and institutions, and ethical procedures are not systematically implemented in funding programs. The connection between ethical reviews and participation remains underdeveloped, as their link is often unspecified.

Ethical reviews require skills and knowledge that researchers and innovators frequently lack. Ethical analyses require familiarity and conformity with standards and an understanding of approaches to build, recognize, and justify ethical dilemmas in light of conflicting values. The notions of “right” and “wrong” are based on moral values (ideals), principles and norms that define standards – identified as “ethical principles” – some concerning individual rights, benefits, harms, fairness principles, and virtues.

Identifying possible ethical issues provides guidance for R&I and helps reflect on its implications. It may also enhance the transparency and accountability of decision-makers and could ead to better processes. As such, ethical considerations help address the complexity, uncertainty, and contestation associated with R&I, making these processes more responsible. Because it is impossible for one single stakeholder group to have a comprehensive understanding of societal risks and uncertainties, identifying and weighing ethical considerations can be supported by involving a more diverse set of stakeholders¹¹. Such complementary perspectives allow for a more thorough grasp of both the risks and potential benefits associated with complex R&I processes, anchored in the lived experiences of affected individuals¹². Thus, all dimensions of R&I, including research funding processes, could benefit from stakeholder participation.

Part I: General Considerations

On participation

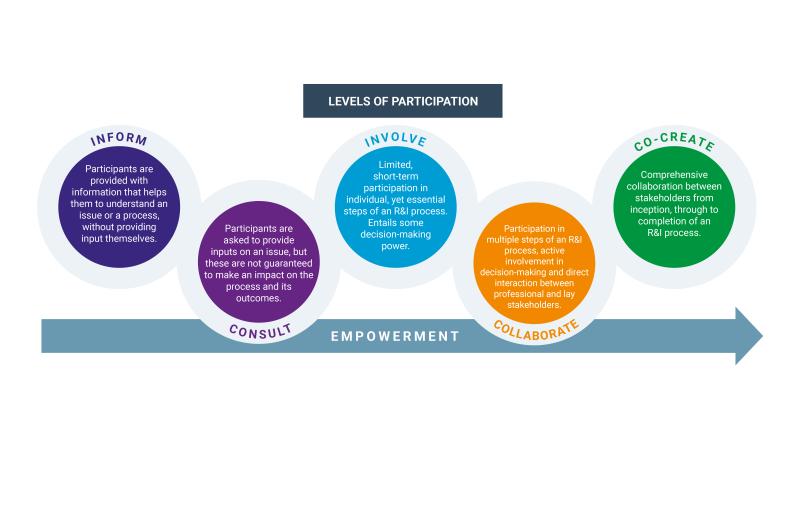

This ethics framework is aligned with the European Commission’s strategy on research and innovation, which aims at “strengthening a common ownership of research and innovation policy and promoting the common research and innovation values” through the co-design and co-creation of R&I activities¹³,¹4. Participation is a crucial part of movements such as Responsible Research & Innovation¹5 and Technology Assessment¹6. While there is no uniform definition, participation is frequently described as a form of engagement that allows (potentially) affected stakeholders to partake in decision-making for R&I¹7. Following the many theoretical approaches building on Arnstein’s ladder of participation¹8, truly participatory practices are arguably different from other engagement practices in that they empower stakeholders to varying degrees to shape decisions in accordance with their own values and worldviews. In this, there is a trade-off between the possible control exercisable

by researchers, funders, policymakers, and so on, and the level of empowerment experienced by other stakeholders. Participatory practices are further distinct from other engagement forms as they require two-way communication between the participant and decision-maker¹9. Thus, when structuring and implementing a participatory process, there are many decisions to be made, all of which have ethical implications.

by researchers, funders, policymakers, and so on, and the level of empowerment experienced by other stakeholders. Participatory practices are further distinct from other engagement forms as they require two-way communication between the participant and decision-maker¹9. Thus, when structuring and implementing a participatory process, there are many decisions to be made, all of which have ethical implications.

There are numerous supporting and opposing arguments for participation²0. As discussed in our overview on ethics, participation is needed to identify and weigh ethical considerations to arrive at more socially desirable and ethical outcomes. Participation is furthermore supported by the assumption that tackling complex public problems requires collective decision-making to foster more effective outcomes²¹ (substantive rationale). What is more, participation is often argued to enhance the trust in, and the legitimacy of, R&I. Stakeholder participation may also lead to an increased support and adoption of outcomes (instrumental rationale). From a democratic perspective, participation may

moreover be considered ‘the right thing to do’ as potentially affected stakeholders can influence how their lives are being shaped (normative rationale). Yet, participation is not always deemed desirable and is often opposed by those who consider that scientific work is already exposed to many constraints both internally and externally (e.g. international competitiveness).

The relationship between participation and ethics can be complex and ambiguous. It differs in each instance, depending on the chosen approaches, types of stakeholder, and aims of the decision-making process. Examples of possible approaches include participatory evaluation, citizen juries, consensus conferences, deliberative opinion polls and citizen advisory committees. While participatory decision-making processes can aim to achieve consensus or compromise, they might also allow for (productive) disagreement as a result of an activity.

Another key issue to address when implementing participatory processes is who exactly should be engaged. Participatory processes are increasingly targeted at “citizens” or “stakeholders“ – terms which are not synonymous, nor do they represent the whole array of potential participants. In any case, it is important to be aware that the terminology chosen for prospective participants has consequences for who may be included – and who excluded. Thus, the language used must be critically reflected and chosen carefully²². For instance, “citizen” also has a legal meaning tied to nationality which might not be intended when employing the term in a participatory process²³. Participants can be of various kinds, extending beyond the traditional expert (scientist or researcher) and including, for example, experts by experience and civil society representatives. Other categories essential to consider, both when defining a stakeholder group and when engaging a specific group of participants, include gender, dis/ability, socio-economic background, age, geographic location, and ethnicity. The relevance of different groups of participants will vary depending on the exact context of the process.

In light of the various definitions, rationales, approaches, roles, and types of participants, a taxonomy is presented in this ethics framework as a guideline and common reference point for our working definitions.

PRO-Ethics identified several needs of RFOs employing participatory approaches. These relate to: the definitions of participation and ethics in R&I; ethical dimensions and potential issues; ethical risks and their mitigation; the need for checklists specifying what to consider when involving participants; and considerations regarding ethical challenges, (structural) biases, and points of attention. Specific issues have also been identified when different interests and types of knowledge intersect, as well as in terms of the methods to be employed. Subsequently, participation should be approached in the context of each individual case, and with appropriate questions addressed.

The perceived benefits and legitimacy of participatory processes differ among stakeholders. There are various factors that play a role in participation, such as: the needs of RFOs and the resources at their disposal; the potential modes of participation and their appropriateness to the task; and the ethical challenges and issues of participation critical to RFOs (identification and representation of participants, avoidance of biases, use of personal data, etc.). All these factors were considered when developing the tools and guidelines in this ethics framework.

Experiences with the ethics framework

In the context of the PRO-Ethics project, nine RFOs experimented with this ethics framework for their stakeholder participation processes. Collective reflections on the framework’s use revealed challenges and potential solutions that may prove valuable for future participatory processes. These ‘lessons learned’ related to: the recruitment of participants; managing commitment and expectations; fostering of dialogue and equal participation; accommodation of vulnerable groups; creation of funding themes with participants; lack of expertise in participatory ethics; and planning, flexibility, and resources.

RFOs indicated difficulties in relation to the recruitment of participants. While they generally aimed for heterogeneous groups that appropriately represented all relevant stakeholders, these were often difficult to determine and subsequently assemble. In piloting participatory processes, the project’s RFO partners selected stakeholders on various criteria, such as their socio-economic background, education, age, religion, ethnicity, and gender (identity). This in turn posed challenges in terms of intersectionality, as participants may identify with multiple stakeholder groups. A possible way forward is to allow stakeholders to self-categorize according to their own understanding of their identity. In addition, because the understanding of ‘correct’ representation tends to vary among different stakeholders, this question cannot be addressed in a standardized manner, but must be considered in the context of each specific participatory process. Still, RFOs must consider whether representation that ‘accurately’ reflects society is desirable at all, given that the politics among participants will then likely reflect the dynamics found in society. For instance, it may be desirable in some cases to give minorities a stronger voice to mitigate power imbalances.

RFOs also found recruitment of their targeted stakeholders more difficult than anticipated. In practice, there is often a disparity between which stakeholders should be involved (in terms of desired representation), and which can be recruited (in terms of willingness, capacity, resources, recruitment efforts, etc.). Not every stakeholder potentially affected by R&I is interested in participation. The RFO partners therefore relied on practical solutions, such as snowball sampling and using multiplier organizations to recruit participants, while acknowledging the drawbacks of such methods (e.g. selection bias). Employing the support of experienced recruiters may also help address some of these challenges.

Managing commitment and expectations posed challenges as stakeholders have different views on R&I, RFOs, and concrete participatory processes. Experiments suggest it is important to understand, and to accommodate, the needs of participants. Some stakeholders may require different forms of participation or may need financial compensation. It proved helpful to transparently communicate everyone’s expectations regarding the roles, scope, purpose, process, and outcomes of the participatory activity. Such expectations may also be made explicit in a (co-created) code of conduct.

Difficulties also emerged during the participation process in relation to organizing meaningful dialogue and equal participation. Equal participation is deemed important to gather values and worldviews relevant to the R&I process, but because stakeholder participation is often characterized by diverse perspectives, this poses the risk of misinterpretation and conflict. Furthermore, some perspectives might dominate discussions as a result of personalities, knowledge, or institutional roles (e.g. citizens vs. scientists). Mitigating knowledge-based domination may require a thematic ‘warm-up’ for both citizens and scientists. Deploying a facilitator who is gender- and diversity-competent could also help mitigate conflict and imbalances by steering discussions and safeguarding the involvement of less vocal participants. Mutual trust among participants can be fostered by choosing an external mediator who takes on a neutral role during discussions. It can also be beneficial to reduce information asymmetries by either offering or withholding information.

The RFO partners also indicated challenges in the accommodation of vulnerable groups²4.This is particularly relevant as participatory processes in research funding often relate to solving real-life problems. The stakeholders affected by these problems may therefore be subject to social injustice, financial issues, or other pressures and risks. Because vulnerability is difficult to define and understand, it is useful to consider the factors that make stakeholders vulnerable, such as their resources, abilities, experiences, identities, values, and worldviews. As stakeholders generally have the best insight into their own vulnerability, it can be helpful to gain their perspective rather than rely on assumptions made by the RFO. RFOs could also help accommodate vulnerable groups by listening to their suggestions, and by addressing the underlying issues that give rise to disadvantages, e.g., through financial compensation, the use of translators, or the enhanced accessibility of meetings.

In the case of stakeholder participation for the creation of funding themes/priorities, some RFOs experienced difficulties determining how to involve both traditional stakeholders (scientists and innovators) and non-traditional stakeholders (e.g. citizens). The RFOs recognized three possible ways to involve both groups: (1) traditional stakeholders propose themes, which non-traditional stakeholders select and contextualize; (2) non-traditional stakeholders propose themes, which traditional stakeholders then select; or (3) themes are proposed and selected collectively. While all three approaches may yield results, RFOs found that collective discussions tended to give rise to power imbalances (e.g. based on expertise and status). Allowing non-traditional stakeholders to propose themes yielded many socially relevant topics, but these were not always considered scientifically relevant. On the other hand, streamlining the process, by allowing traditional stakeholders to propose themes for non-traditional stakeholders to select, ran the risk of tokenism due to the limited decision-making power of the latter group. As such, all approaches have advantages and drawbacks, and the appropriate approach likely remains context dependent.

While skills and knowledge on ethics and participation are believed to improve stakeholder participation, RFOs frequently lacked ethical and participatory expertise. RFOs indicated that the ethics framework is helpful, but that external support from ethicists, facilitators, and recruitment agencies can improve the quality of participation. It is nevertheless helpful to recognize that organizing stakeholder participation benefits from a ‘learning-by-doing’ approach that is flexible and open to feedback from its participants. RFOs subsequently benefit from people with the right mind-set, i.e., openness, social skills, and the willingness to learn and engage.

Lastly, it is important to stress that, while the ethics frameworkstrives for the highest ethical standards, it may not always be possible to meet these in practice. Organizing stakeholder participation is an uncertain process that does not always unfold according to plan. One RFO remarked that “these processes seem way more resource consuming than thought in the beginning”. Participatory processes are also dependent on external factors (e.g. regulations, operational planning). All these challenges indicate that it is helpful to have a surplus of resources available, and to have back-up plans in case flexibility is needed.

Part II: Tools & Guidelines

Considering the complex relationship between participation and ethics, how should participation be organized and framed? Rather than providing broad criteria, this ethics framework offers a list of questions for consideration. The purpose of the PRO-Ethics Tools & Guidelines is to provide a context-sensitive roadmap in the form of questions for the design, implementation and evaluation of stakeholder participation. Because different contexts offer different opportunities and constraints, this ethics framework provides guidelines as opposed to rigid rules. The questions, considerations, and classifications below address the ethical aspects that need to be considered when planning different types of participatory activities: who, when, how, and why does it matter?

Consideration of these questions is intended to define how stakeholders can be identified and invited to participate in R&I processes, using a pluralistic, ethical approach that may provide added value as laid out above. Ethical issues are guiding these tools, leading to a list of dimensions and questions to address as a roadmap for the diversity of methods and options for participatory approaches. The purpose of this ethics framework is to provide tools and guidelines to determine whether participation is warranted and what actions and considerations should be undertaken in order to ensure that participation is inclusive and ethical. The most suitable participatory path in each instance derives from a consideration of the context and the specific needs of both the institution undertaking it and of the R&I process that it is applied to. Although this ethics framework is designed primarily for RFOs, it may well prove helpful for other organizations.

In the following, we offer a set of questions and associated actions to consider when designing, implementing and evaluating participatory processes:

Each section includes an indicative timeline which has been highlighted for each specific subset. These indications serve to identify when a specific action is to be undertaken. They may be cumulative in the case of an iterative action, taking place at different stages of a process:

BEFORE

participation

DURING

participation

AFTER

participation

The framework is concluded by a glossary of key terms used when discussing participation in research and innovation. This glossary aims to support the development of a common language and shared understanding, and thus facilitate the effective implementation of such processes to a high standard.

A. How should participatory processes be structured?

ACTION A1:

Understand the structural constraints you are operating under

Reflect on the structural context you are operating in and outline existing dependencies that affect the implementation of your participatory process. Identify existing rules and procedures relevant to your process (institutional, legal, and other) and investigate how much flexibility you have to adapt these. Determine what decisions you may make independently, where you need to secure buy-in from other institutional actors, and how much decision-making power you may relay to participants. Secure a mandate and resources (time, budget, personnel) to implement the participatory process.

ACTION A2:

Identify and clarify the expected contributions

Identify why you and potential participants are interested in collaborating, what roles each stakeholder might have, and what types of knowledge and perspectives are sought. This also needs clarity on the expected goals and impacts of the process. Transparently clarifying these from the beginning and throughout the process helps to manage and align expectations on both sides, particularly regarding the impact of the process and how interactions should be structured. This also helps frame, justify, and outline participatory processes for more focused, ethical, and appropriate implementation.

ACTION A3:

Allow for flexibility when planning the participatory process

Stakeholder participation benefits from being organized in an iterative and agile process. Due to its complexity, unexpected nuances and concerns usually arise in the making. This calls for organizational flexibility, which can be fostered by proactive approaches to risk management. Sufficient time and resources must be allocated to the participatory process. These resources and chosen participatory methods²5 contribute to the flexibility and quality of the process and need careful consideration.

Identify the potential social, political, institutional, economic, environmental, or other impacts that R&I processes may have, including potential negative impacts stakeholders would like to avoid. Try to be comprehensive and cover all potential stakeholder groups in your assessment. Impacts are best anticipated in inclusive settings and can be better understood by involving the stakeholders that may be affected. Impacts should be listed and related to the design and outcomes of participatory processes. Consider collectively what steps should be taken to mitigate risks and realize desirable outcomes.

Be mindful of the fact that all impact assessment models have a specific scope and a limited focus. They are best seen as tools to support a better structure and understanding of your participatory process and the outcomes you want to achieve. Good online resources to consult on impact assessment include:

https://www.betterevaluation.org/ https://www.fasttrackimpact.com/https://impact.nwo.nl/en/working-with-an-impact-plan

--LINK FEHLERHAFT

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/690031/EPRS_STU(2021)690031_EN.pdf

https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/swd2021_305_en.pdf

SHOWCASE

VDI/VDE-IT learned that the identification of expectations should be one of the first steps when structuring participatory processes. Participants in their pilot expected concrete solutions that would solve their everyday problems. Yet, in many cases this was deemed too optimistic by the funding organization. Recurring clarifying conversations and codes of conduct helped align expectations about the process, its scope and goal, the intended outcomes, and everyone’s concrete responsibilities.

B. Which type of activity is targeted by the participatory process?

An appropriate context, type and timing for the participatory process has to be selected (see below). This can be very limited, covering only one activity within a larger process, or it can be comprehensive, beginning at the planning phase. Build on impacts defined in A4 and take into account the stakeholders’ relationship with, and potential contribution to, the R&I process.

Research funding organizations have a special position in R&I ecosystems. On top of funding and supporting scientific projects that build on or employ participatory methodologies, they can also involve stakeholders in RFO-specific activities, such as:

- Developing R&I strategies

- Setting funding priorities

- Defining and formulating funding calls

- Evaluating project proposals

- Mentoring R&I projects

- Monitoring R&I projects

- Evaluating R&I projects

There are many different participatory formats, including citizen juries, citizen advisory boards, consensus conferences, focus groups, deliberative opinion poll, negotiated rulemaking, participatory evaluation, and so on. Good online resources to consult on participatory formats include:

https://involve.org.uk/resources

https://participedia.net/

Cos4Cloud Methodological Guide (Co-Design): https://zenodo.org/record/7472450#.Y9Pqii8rzs3

Participatory AI for Humanitarian Innovation: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Nesta_Participatory_AI_for_humanitarian_innovation_Final.pdf

Schuerz, Stefanie (2023): Research and Innovation Funding Cycle.

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8096861

Reflect on any barriers for participation that might exist for different groups of stakeholders and how to address these. Barriers can include location and venue accessibility (e.g. geographic location / distance, connectedness via public transport, and architectural design / wheelchair accessibility); the accessibility of the technologies employed for the activity (e.g. digital technologies and associated costs); the flexibility needed to participate in a process (e.g. in terms of time and money) and what your process might compete with (e.g. paid employment, care duties, health management and recuperation time, other volunteer work). Other potential barriers might arise from power structures and institutional exclusionary practices (e.g. imbalances arising within a group of participants, the participation of certain populations being vetoed by decisionmakers, or certain groups excluding themselves due to discomfort or fear of certain institutions). Develop concrete solutions to address these barriers, such as providing childcare on location, choosing accessible venues, and covering associated costs. Think about which participant groups you are reaching and which you are excluding.

SHOWCASE

UEFISCDI used a world café approach to involve citizens in validating and enriching parts of the Romanian National Strategic Agenda for Research. This list of societal challenges and leading questions, developed by experts, was aligned with the needs and experiences of citizens. While the take-up of citizen inputs couldnot be guaranteed beforehand, some inputs were integrated in the agenda after all, with one entirely new topic developed from the citizen inputs. In this, the format of engagement was helpful as it allowed for rich exchange and enabled the agency to include a topicthey had not considered before.

C. Which types of participants are targeted?

It is important to understand which stakeholders it might be important to involve in a process, and why. This could mean including stakeholders affected by, or with, specific knowledge or experience of an issue, and considering the specific role and relative power stakeholders have within a system or process. It also entails a broader reflection on aspects such as gender, age, socio-economic background, dis/ability, geographic location, as well as stakeholders’ proximity to the R&I process. These specifications allow for a better understanding of the field and the identification of groups that may have been overlooked. It also helps to understand the potential needs of participants to meaningfully take part in a process. Mapping potential stakeholders and their interests ensures that the type of participatory process appropriately addresses both the context and the stakeholders involved²6. Consider what type of representation is needed to obtain the desired contribution. For instance, do participants need to reflect the diversity of society, or should the process focus on specific stakeholders? As an example, matters of representation become important when interested in specific user groups or marginalized stakeholders.

SHOWCASE

FFG used an online survey to broadly consult people living in Austria in the definition of topics for a specific funding call focused on health topics, climate change, demographic change, and ICT solutions. As these topics impact all Austrian residents to some degree, FFG chose to make the survey openly accessible to all. They recruited participants through internal and external efforts and promoted the survey through multiplier organizations and through their newsletters. FFG learned that recruitment efforts benefit from organizational and financial flexibility as a number of surprises and additional costs emerged. This included much richer qualitative inputs than expected, but also significant self-selection bias impacting the make-up of the participant group.

After potential participants have been identified, it is important to consider how they should be recruited, taking into account stakeholder representation, selection bias, and feasibility. Identification and recruitment of participants often takes more time and investment than anticipated and may become a prolonged, iterative process in more lengthy participatory endeavors. Reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of different recruitment techniques (e.g. feasibility versus selection biases), and target your approach based on stakeholders’ specific needs as identified in C1. While recruitment can be challenging, stakeholders are more inclined to participate if the process is in their interests. Timing can be a decisive factor. Consider, for instance, whether holidays or other factors may restrict a participant group’s involvement. Possible recruitment techniques include:

- Existing organizational networks: The organizer’s existing stakeholder network provides an opportunity to recruit participants. Stakeholders can, for example, be contacted through social media or newsletters.

- Snowballing techniques: Asking participants for referrals to other potential participants can enlarge the existing pool of participants.

- External recruiters: Recruitment can be outsourced to experienced parties. Make sure that recruiters are sensitive to ethical issues relating to stakeholder participation.

- Multiplier partners: External partners, such as municipalities, intermediaries, and influencers, can help recruitment efforts by providing access to their stakeholder network. Persuading these multipliers to collaborate tends to be easier when they share similar interests with the participatory process.

D. What are ethical issues and risks?

With clarity on the participatory process and potential participants, it becomes easier to assess potential ethical issues and determine where and how a process should be adapted. Ethics experts could help identify, understand, and mitigate ethical issues.

Consider the following potential issues in relation to your R&I processes: In project proposals:

- Issues of human dignity, power, intellectual property, privacy and data protection, transparency, and biases (e.g., gender bias, bias towards the able-bodied, etc.) should be considered when planning the process and outcomes of research and innovation.

- In project executions: Issues relating to personal data; discrimination; stigmatization; fixation on technology acceptance; vulnerable groups; privacy; safety; social responsibility of researchers; informed consent; social roles in the application context; use of ethically sensitive findings; manipulation and guardianship through technology.

- In evaluation processes: Common ethical risks in relation to stakeholders’ legitimacy, lack of ethical expertise; communication of funding calls; conflicting interests.

Consider the following issues that may arise in general:

- Informed consent:

- Informed consent procedures should be employed to build a baseline understanding of the process among those involved.

- Ensure that you choose an appropriate informed consent process and format for the target group.

- Use accessible language, keep the document to a reasonable length, and consider creative approaches such as movies and comic strips, or dynamic informed consent to address groups farther away from the R&I system.

- Financial compensation:

- Determine if, to whom, and how much financial compensation should be given.

- Compensation should take into account potential barriers to participation, but shouldn’t be an incentive in itself.

- Determine if, to whom, and how much financial compensation should be given.

- Methods:

- When participation is made a mandatory requirement for funded projects, this might raise the hurdle for diverse and new institutions to access funding. Support and training could mitigate this risk.

- Identify the suitability of the selected participatory process regarding i) if participation is warranted in the given process; ii) if stakeholder participation would benefit from additional support.

- Knowledge / awareness:

- Consider what might be needed to ensure that participants understand R&I. For example, a warm-up exercise might be provided for participants. Ensure participants have enough time to process new information.

- Identify what knowledge may be helpful for the participatory process. Try to foresee group dynamics that may emerge as a result of information asymmetries. Ensure you have (access to) the required expertise to identify and address ethical issues.

- Disadvantaged stakeholders:

- Identify if, who, and how stakeholders may be disadvantaged. This can partly be determined on the basis of participant input.

- Engage with disadvantaged stakeholders prior to the participatory process to understand their needs.

- Customize participatory processes to disadvantaged stakeholders so that they can participate in a meaningful way.

- Research integrity:

- Identify if, and how, the participatory process might affect the researchers’ integrity.

- Align the participatory process with frameworks, standards, and/or codes of conduct on research integrity

- Assess the overall risk to actors in the process, including

- physical (direct harm, long-term harm)

- psychological (traumatizing methods, sensitivity of questions, ...)

- social (stigmatization, discrimination, ...)

- data protection, privacy, confidentiality

- the insurance status of each participant

SHOWCASE

RCN concluded that ethical issues and risks must be explored together with stakeholders. They therefore organized three workshops to collectively reflect on what challenges emerge in participatory contexts, and how they, as a research funding organization, can better align ethics and citizen involvement. They identified issues in relation to data privacy and the compensation of participants, which both required further consideration. Innoviris encountered political interference in their stakeholder engagement process caused by misaligned expectations and exacerbated by power differentials. They concluded that it was important to involve key stakeholders from the very beginning and maybe even seek contractual agreements with all parties, especially political ones, detailing the plans from the outset in order to avoid similar roadblocks.

E. How can equal and meaningful dialogue be fostered?

Ensure that the design and implementation of participatory processes fosters equal and meaningful dialogue among participants. Contemplate whether an experienced (external) moderator would improve the process. Think about forms of representation, types of participant, and reciprocal relationships, taking into account possible power imbalances. The following non-exhaustive list of considerations are important:

- Representation: Consider who is excluded and included by reflecting on the balance between diversity and representation (proportionality). When selecting a group of participants, take into account possible (over-)representation of minorities.

- Power: Make sure all participants are heard and try to reduce power imbalances. These imbalances may result from the participants differences in personality, capacity, knowledge, and resources. It can, for instance, help to reduce information asymmetries by providing or withholding information. In addition, try to identify any conflicts that may need to be navigated. A skilled facilitator or ombudsperson can play an important role here.

- Empowerment: Take measures to enable your participants to actively participate in, influence, and benefit from the R&I process and its outcomes. Allow them to make decisions and develop ownership of the process.

- Exploitation: When including minorities and/or vulnerable stakeholders, ensure that they are not negatively affected by the participatory process. If needed, provide forms of adequate compensation either before, during, or after the process, on a case-by-case basis.

- Vulnerability: Recognize that there are many aspects to vulnerability that are often difficult to identify. Pay specific attention to aspects that give rise to vulnerabilities such as one‘s experiences, abilities (including language skills), identity, resources, values and worldviews. Participants are best placed to recognize whether they are vulnerable. Trust their judgement and accommodate for their vulnerability.

SHOWCASE

Power imbalances may impede equal and meaningful dialogues, and frequently emerge from information asymmetries – for instance between scientists and citizens. VDI/VDE-IT therefore deliberately considered whether they should hand out information, to whom, and when. Information management and active facilitation proved useful for fostering constructive debates in which everyone is heard.

F. How should participatory processes be monitored and reflected upon?

ACTION F1:

Monitor and collectively reflect on the participatory process and outcomes

To safeguard ethical aspects of participation, it is important to monitor potential issues during the implementation and evaluation of a process, as laid out in action-set D. This can be done using qualitative and quantitative performance indicators and through continuous feedback from participants. Continuously and collectively reflecting upon expected or unexpected performances and outcomes will help to improve ongoing and future participatory processes. Expectations may be adapted if needed, following a possible deviation from pre-set monitoring indicators.

This action is complementary to A2 and A3

ACTION F2:

Reflect on the following aspects

- Verify if and how matters of representation and inclusion are/were addressed throughout the participatory process.

- Consider the balance of input from participants in the decisions made during participatory processes.

- Determine whether the goals of the participatory process will be or have been achieved. Identify how the biases of your participatory activities affected the process and its results.

ACTION F3:

Launch a transparent process allowing participants to interact and reflect

Depending on the scope of the participatory activity and organizational capabilities, a collective reflection on the participatory process helps to develop an understanding of the participants’ experiences. This can for instance be achieved through a short focus group or survey. Such feedback should be used as the main assessment of the process, indicating potential needs for improvement.

ACTION F4:

Communicate how the input of participants is used

Reflect on the input of participants, its added value, and how it did (not) feed into outcomes. Why and how were certain decisions made? Communicate this to participants, and ensure they feel valued. In some cases, this may include a financial compensation (see also action D) or an official acknowledgement.

ACTION F5:

In view of future reference, all reflections answering the framework’s actions could be documented and saved

It may be beneficial to document stakeholders’ answers for the benefit of future participation activities. This also helps with accountability.

SHOWCASE

All pilots reflected upon their participatory process and recruitment efforts. They reflected on their challenges, success stories, and lessons learned. Many of these insights emerged from collective reflections on participants’ experiences. These insights were documented for future use. For example, CDTI concluded that they needed a slight change in the scope of their participatory process to reshape the societal impact of their funding efforts.

INFORMED CONSENT IN THE CONTEXT OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES

In the last two decades, the notion of informed consent (IC) has gained prominence in the context of technology development and use. It is increasingly agreed that new and emerging technologies come with potential risks that will only emerge through their use. Some ethicists of technology have therefore proposed to see the application of these technologies as a kind of research with human participants, with similar principles applying as in more traditional research. However, where it is relatively clear whose consent is needed in research with human participants, the group of people potentially affected by new technologies cannot clearly be demarcated. In such situations, a more collective equivalent of informed consent is needed, such as the requirement for oversight by some democratically legitimized regulatory body.28 A clear application of the principle of informed consent showing its limitations in broadly deployed technology is the use of cookies on websites. Under EU regulation, websites either ask visitors to accept or reject cookies, or they are explicitly warned that by using the website, they are also consenting to the use of cookies. However, if people want or need access to a website, they are often forced to accept cookies. Similarly, through deceptive or overwhelming design, users are often intentionally disincentivized from engaging with the process and as such not truly ‘informed’. This points to a huge challenge for digital technologies in particular: in our digitalized world, there is immense pressure to use particular technologies in order to participate in society, while such use is often tied to surveillance and the collection of personal data. This issue will presumably be exacerbated by the wide deployment of AI and especially AI assistant technologies with deep insight into the lives of individuals. As such, it is essential to develop these digital technologies and relevant governance structures in a transparent and privacy-sensitive way. Approaches like human-in-the-loop design, trustworthy AI and explainable AI aim to make the technology itself more sensitive to important ethical values, rather than placing the responsibility for ethical functioning of the technology with the user.

Glossary I

The categories and definitions outlined below reflect the work undertaken in PRO-Ethics. They emerged as common references during the project, and are important for the implementation of ethical participatory processes, particularly in relation to the activities of research funding organizations.

In the context of our work, bias is relevant in two ways: First, as often unconscious preconceived opinions, beliefs, or attitudes that influence how stakeholders in R&I define and address problems, set up processes, and perceive and interpret data. This might entail a preference for the inclusion of particular stakeholder groups over others (or a perceived greater validity of some perspectives), a predilection for specific outcomes, and an overall skewing of the process towards certain – often hegemonic – power structures. Second, as systematic errors in the vein of statistical bias that distort the process as well as the collected data and its analysis. While often unintentional, flawed methodologies, selection biases and information biases can have significant ramifications for the quality of an R&I process and its outcomes, while also negatively impacting its participants. Thus, it is essential to be mindful of potential biases and take active steps to identify and address them in order to ensure the quality and equality of an R&I process.

While „citizen“ is not a term that should be employed uncritically, we decided to draw on this category as an established umbrella term that includes the general public, lay people, and citizens as persons (or collectives) with civic expectations. Moreover, since end-users can be categorized as citizens as well, this distinction serves to underline the general dimension of involvement, referring to the broader sense of “public participation”.

Civil society organizations are not-for-profit organizations that may represent specific groups of citizens, but whose knowledge and leverage differs to that of individual citizens. They may defend interests, often professional interests (trade unions), or causes (e.g., animals, environmental issues), or rights (e.g., minorities, women).

In the context of R&I processes, communication refers to the sharing of contents and results of R&I activity in an accessible manner, increasing its public visibility. It is distinguished from dissemination by its primary target groups, as dissemination is targeted more towards a scientific audience, but also policymakers and industry representatives. Both communication and dissemination tend to be one-way exchanges of information towards any type of stakeholder.

We use co-creation to encompass comprehensive collaboration between all stakeholders of an R&I process, from its inception to its conclusion. Hailing more from the context of an R&I project, co-creation covers all stages of the research cycle, from the definition of a research question to the evaluation of a project and assessment of its impact. While this has not yet been similarly established as a valid approach, this process can be mirrored in the context of the R&I funding cycle, starting from the development of the R&I funding strategy and ending with the evaluation and impact assessment of funded projects and the overall funding program. As an umbrella term, co-creation also covers the concepts of co-design (collaboratively defining a problem and its solutions by designing technologies, processes and solutions), co-production, and co-development.

While collaboration broadly covers the process of people or organizations working together to achieve a goal, in the context of our framework it is important that collaboration is equal and meaningful, i.e., allow all involved stakeholders to contribute towards and impact the process and its outcomes.

Processes of engagement (see definition of ‘engagement’) where any group of citizens or stakeholders are asked to provide input on an issue, process, policies or programs. These inputs are not guaranteed to be taken up in a meaningful manner, in that they make an impact on processes and their outcomes.

Diversity as a term reflects the many different ways we understand and categorize people (e.g., according to gender and gender identity, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, dis/ability, socioeconomic status, etc.). Inclusion is about providing equal access to take part in a process or activities. Thus, diversity in participation is about including a range of perspectives and experiences to create outcomes that work for more than just a few. In this context, equality refers to everyone being treated equally and receiving the same opportunities and resources, while equity is about addressing individuals’ specific needs. It is essential to address bias and discrimination to achieve both equality and equity for diverse groups of people, but also to ascertain the quality of R&I and mitigate potential harms it may create³¹

In tort law, a duty of care is a legal obligation prescribing adherence to a standard of reasonable care to avoid careless acts that could foreseeably harm others and lead to claims of negligence. A duty of care can apply in many different contexts, ranging from a school’s duty of care towards its students and an employer’s duty towards its employees, to businesses’ duty of care towards consumers who buy certain products. In the context of participatory processes, the initiators of these processes have the duty to take measures to prevent participants from being harmed by or as a result of their participation. A duty of care may be considered a formalization of the social contract, where a person or an entity who is in a position to prevent others from being harmed has the responsibility to do what is in their ability to prevent this harm from materializing.

Empowerment is about enabling individuals and groups to actively participate in, influence, and benefit from R&I processes and their outcomes. It aims to distribute power equitably and in turn have a positive impact both on the concrete processes at hand and wider society. Empowerment can entail the provision of knowledge, ensuring that people have access to and an understanding of scientific findings. And it can entail participation, which is about inviting a broad range of relevant stakeholders to the table – including also underrepresented and marginalized groups – while ensuring that all participants in a process are heard and have a hand in shaping the course of the R&I endeavor.

End-users are the (presumed) groups and individuals intended to make use of the end product (including solutions and services) of an R&I process. While the concrete (groups of) end-users cannot always be foreseen in their entirety, assumptions about their needs are always inscribed into a technology, process, service or solution. Engaging potential end-users in the development of R&I is intended to better meet their needs, and thus heighten the chance of the outputs to be useful and used.

In this document, engagement is used as an umbrella term for different types of one-way and two-way exchange, as well as collaboration between stakeholders from R&I (such as professional researchers and research funding organizations) and stakeholders beyond the R&I system (such as citizens, end-users, civil society organizations, NGOs and so on). This may include forms of communication, consultation, or more intense approaches to participatory engagement such as co-design and co-creation.

Ethics is the discussion of and reflection on moral values and norms (in short: morality). The adjective "moral" indicates that those values and norms have a special status, typically taking the form of obligations and prohibitions. Their special status is manifested by the fact that moral rules are accompanied by praise and blame, rewards and punishments, to motivate people to live according to these norms and values³². The adjectives ethical and moral are often used interchangeably.

This category encompasses several types of evaluation: evaluation of project proposals (i.e., the ethical and scientific evaluation) as part of the selection process intervening in funding schemes; the interim and ex-post evaluation for projects and programs that received funding; and program evaluation. Evaluation reflects on the implementation and results of an R&I endeavor to ascertain its overall quality, and can focus both on processes and outcomes/results. In contrast, impact assessment always focuses on the broader long-term effects of an R&I process.³³

This category serves to identify individuals who are enrolled as internal or external experts in R&I processes. In the context of this document, we include both lay and professional experts in this category. For instance, citizens may be involved in an R&I process as ‘experts by experience’, providing insights into their lifeworlds and value systems. Experts may also be individuals with any sectoral/disciplinary expertise (e.g., with a background in medicine, psychology, sociology, philosophy — among others). Consequently, participants might bring different kinds of expertise and different types of knowledge (e.g., tacit, formal, endogenous, living world, etc.) to an R&I process.

Current AI systems often involve deep learning. While deep learning has allowed for significant progress in artificial intelligence, in comparison to traditional machine learning methods such as decision trees and support vector machines, deep learning is comparably weak in explaining its inference processes and the way its decisions come about. For that reason, deep learning algorithms are typically considered a black box by both developers and users. This lack of transparency has led to the development of ‘explainable AI’ (also XAI), in which explainability is seen as a desirable feature or even ‘must have’ of AI systems.³4 Explainability is considered especially relevant when AI is used as decision making tool in professional context, where it is important for its acceptance that people know how a decision came about.³5 Notions that are related to explainability are interpretability, understandability, and to a lesser extent also transparency. While these notions may have slightly different meanings, they all refer to the need to break open the black box of AI system.

As a concept related to diversity, equality/equity, and inclusion, fairness encompasses ensuring equal access to resources and opportunities, unbiased decision-making processes, and outcomes that dont unjustly advantage or disadvantage certain groups. Like other ethical principles covered here, the specific interpretation and implementation of fairness may vary depending on the context.

Glossary II

The term human-in-the-loop (HITL) was developed in the context of artificial intelligence (AI). It can refer to the role of human intelligence in machine learning or simulation, but also in the use of otherwise autonomous systems. When used in machine learning, the role of the human in the loop is to select the most critical data that is needed to improve the performance of an AI system (i.e., to improve its learning). In machine learning without any human in the loop, data is selected via random sampling, which may not lead to the most effective and efficient learning of the algorithm. In simulation, HITL is also referred to as interactive simulation, where the physical simulation includes human operators, such as in a flight or a driving simulator. In the context of autonomous systems, HITL is meant as a safeguard to prevent that AI-based systems autonomously take decisions with high stakes, such as in the case of autonomous weapons or autonomous cars. In those contexts, HITL is operationalized via the principle of “meaningful human control”, according to which systems should be designed in such a way that humans and not computers and their algorithms should ultimately remain in control of, and are thus morally responsible for, relevant decisions about possibly lethal operations.³6 This involves a twofold design requirement: (1) the autonomous system should be responsive to the relevant moral reasons of the humans designing and deploying the system and the relevant facts in the environment in which the system operates; and (2) the system should be designed in such a way as to grant the possibility to always trace back the outcome of its operations to at least one human along the chain of design and operation.

Human-centered design (HCD) is an approach which enables designers, developers, and engineers to focus their projects on the prospective users of the products or services they are working on. It emerged in the field of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) as an approach to avoid the design of products or services that people cannot or do not want to use. HCD can be used as an umbrella term to include a diverse range of approaches.³7There is also a standard for Human-Centered Design Processes for Interactive Systems from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), which describes the following key principles: To start with an explicit understanding of prospective users and their tasks and environments; to involve prospective users throughout the process of design and development; to involve prospective users in timely and iterative evaluations and to let these evaluations drive and refine the process of design and development; to organize an iterative process; to view the user experience holistically, e.g., not as usability, but also as people’s aspirations and emotions; and to organize a multidisciplinary project-team.

Informed consent (IC) is one of the fundamental ethical principles for research involving human participants. The principle aims to ensure that no person can be made a research subject without free and voluntary consent and with full information about what it means for them to take part. The principle is also key in medical decisions, where patients should always give consent to treatment after being given information about the treatment or diagnosis and its potential risks. In both research involving human participants and in medicine, securing informed consent is a formalized requirement before research or treatment can take place. In recent decades, alternative approaches to IC have been suggested that better address the needs of participants and account for the social embeddedness of both the stakeholders and the processes of R&I. These include new and more accessible formats for mediating IC procedures (including movies and comics), but also approaching informed consent as a continuous process in need of adjustment due to the unpredictability of R&I projects. Apart from these more formalized procedures, informed consent is increasingly also referred to in contexts beyond research involving human participants or medicine, to warn against potentially exploitative technologies that are enforced upon people against their wish.

Intellectual property rights (IPR) are the rights given to persons over the creations of their minds, such as inventions, literary and artistic works, designs, but also symbols, names, and images used in commerce. IP can be protected in law e.g. via patents, copyright and trademarks, which enable people to earn recognition or financial benefit from what they invent or create. In the context of innovation, intellectual property rights aim to strike a balance between the interests of innovators and the wider public interest. Without a system of IPR, companies are allegedly less willing to invest in the development of new products, if the monetary benefits of these efforts are not somehow protected.38In research with low Technology Readiness Levels, discussions on intellectual property mostly concern authorship of scientific publications. Common standards in research integrity prescribe that authorship should only be granted to a person if he or she has concretely contributed to the paper, often via a CRediT statement accompanying the paper.³9 In the context of participation, it is not always easy to demarcate the participants’ contribution to the end product. Recognition of participants’ efforts may require that participants are granted authorship. A too strict view on who deserves authorship may misrecognize participants’ contribution, even if that contribution has not been primarily an intellectual one. In any case, it is important to set up clear procedures – and, where relevant, legal contracts – from the very start of a collaborative process, to ensure clarity and transparency over each contributor’s rights over a final product.

Impact assessment focuses on the longer-term and broader effects of an R&I process. It entails the definition of specific qualitative and quantitative outcomes and indicators for achieving impact, as well as instruments to measure these indicators. Evidence is then gathered and analyzed to show concrete results. Depending on the concrete focus of an R&I process, it might aim to achieve societal, political, institutional, scientific, economic, environmental or technological impact. As impact necessarily unfolds over time, change usually unfolds beyond the lifetime of an R&I process, making it difficult to substantiate.

The systematic observation of the implementation of funded projects and their results in the context of RFO funding schemes. Monitoring is usually carried out internally with support by external experts, e.g., for interim or final reviews. Ex-post monitoring of results can also involve other stakeholders, in addition to the involvement (feedback) of program beneficiaries.

Participants are defined as persons who take part in participative processes. In this document, we primarily use this term for non-traditional stakeholders of an R&I process such as citizens in the broadest sense, (end)-users of a technology, residents of an area, people affected by an issue, entrepreneurs, project beneficiaries, and so on. Participants are engaged in such processes due to their specific knowledge, perspectives and/or interests they bring to the table. Participants can be individuals or representatives of institutions or groups and may include vulnerable groups such as patients, children, or older adults. Often, there is an overlap in categories of participants, as individuals may draw expertise from different fields and experiences. In each instance, it is important to develop an awareness of the characteristics of those participating, and address them in the design and implementation of a participatory process.

While there is no uniform definition of participation, the term is often described as a form of engagement that allows (potentially) affected stakeholders to partake in decision-making for R&I. There is a graduation to the intensity of participatory processes, ranging from limited and short-term involvement to a comprehensive collaboration between all stakeholders of an R&I process, from inception to completion. Truly participatory practices empower stakeholders to shape decisions in accordance with their own values and worldviews.

Privacy is a fundamental right that refers to a persons ability to control their personal information and decide when, how, and to what extent such information is shared with others. There are clear regulations and compliance procedures structured by the GDPR and other relevant national and international law, which entail provisions for the collection, processing, dissemination and storage of personal data and the gathering of (informed) consent. In participatory R&I processes, informed consent is especially important as it opens up the conversation to consider the focus and context of a process, its goals, any associated risks, the intended scope of participation and roles of involved stakeholders, as well as the expectations people bring to the table. It is an essential tool for creating transparency from the very outset.

EC Reference Documents

- 4.1 Rules & codes of conduct

- HE Regulation 2021/695: Eligible actions and ethical principles (Article 18) and Ethics (Article 19)

- HE Model Grant Agreement: Ethics (Article 14 and Annex 5)

- Statement by the Commission on research activities involving human embryos or human embryonic stem cells

- EU Charter of Fundamental Rights

- ALLEA European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity

- Global Code of Conduct for Research in Resource-poor Settings

- 4.2 General guidance

- How to complete your ethics self-assessment

- Guidelines on serious and complex ethics issues4.3 Standard operating procedures

- Guidelines for Promoting Research Integrity in Research Performing Organisation

- Standard Operating Procedures for Research Integrity

- Data Protection Decision Tree

- Designing and implementing a research integrity promotion plan: Recommendations for research funders

- 4.4 Domain-specific guidance

- Guidance note on potential misuse of research results

- Guidance note on research focusing exclusively on civil applications

- Guidance note on research on refugees, asylum seekers and migrants

- Ethics and data protection

- Ethics in Social Science and Humanities

- Position of the European Network of Research Ethics Committees (EUREC) on the Responsibility of Research Ethics Committees during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Research Ethics in Ethnography/Anthropology

- Roles and Functions of Ethics Advisors/Ethics Advisory Boards in EC-funded Projects

- SIENNA Ethical guidance for research with a potential for human enhancement

- Guidelines on ethics by design/operational use for Artificial Intelligence

- European Network of Research Ethics Committees – EUREC

- European Network of Research Ethics and Research Integrity – ENERI

- The Embassy of Good Science• The European Network of Research Integrity Offices – ENRIO